SECTION TWO

The letter I wrote for my proposal will help explain this panel, endurance, and the next one, truth.

LETTER REGARDING OUR HISTORY

Dear members of the Design Review Board, Planning Commission, Planning Department, and Ukiah City Council,

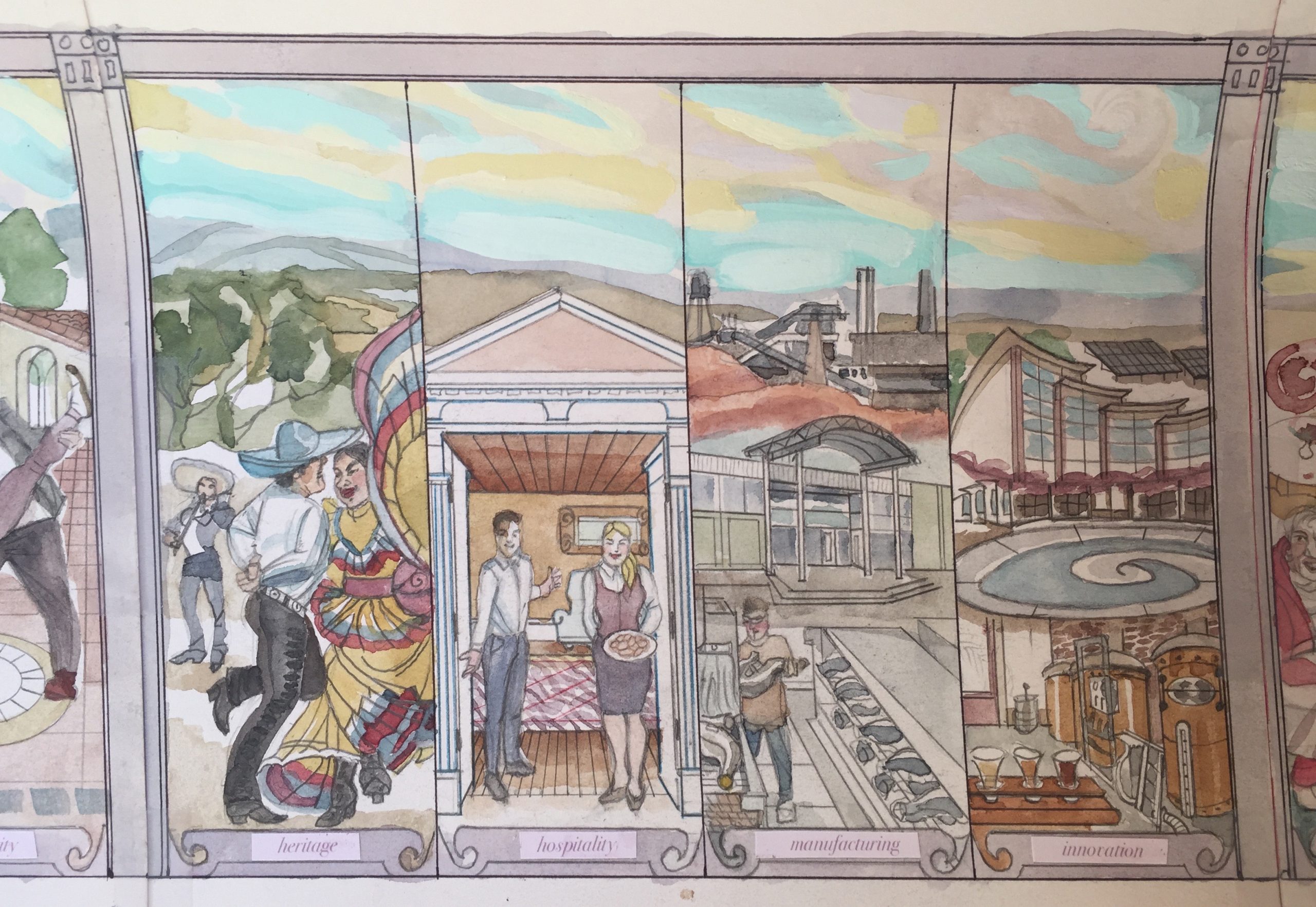

Prior to being selected by the arts committee, I worked intensely for weeks to refine my mural concept for review. The historical research was fascinating and I enjoyed figuring out how to represent complex events through imagery. When you look at my sketches I think you will be happy to see so many of Ukiah’s stories and businesses past and present represented on this big “canvas.”

While every subject in the mural has a rich background and some of the descriptions will probably surprise and delight you, the themes will be familiar. There is just one part of the story that requires me to explain my approach.

Ukiah’s new Public Art Policy Section V. Non-Discrimination states:

“The City recognizes that cultural and ethnic diversity is essential in programs sponsored by the City, and seeks to be inclusive in all aspects.” The policy goes on to prohibit discrimination against an artist or a donor.

City of Ukiah Public Art Policy

Please allow me to describe how I feel it also relates to subject matter.

The stated purpose of this project is to express “pride in our unique and diverse community” and “a positive sense of the future,” as well as to feature the natural landscape around us.

My method of revealing our diverse community is to show our history and our accomplishments. Of course, this story is not just about us, the living.

The story of this place, this rich river valley in the coastal ranges along the Pacific Ocean, is a story that reaches back in time. It is a story of millennia and of the people who made that plentiful environment their home. They lived here for more than 15,000 years. Hispanic and Caucasian people have been here in numbers for less than 200 years. People of Asian and African descent have found this place, and now we are all together.

But the story of how this played out contains a grim reality that shouldn’t be ignored

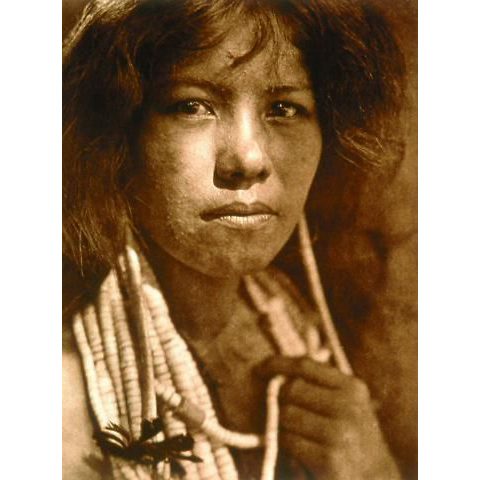

Photo of 16-year-old Pomo Girl, by Edward Curtis, 1924

We know her identity as Frances Jack, from White Wolf James, who knew her later in life.

In 1800 there were some 15,000 native people of multiple tribes living in Mendocino County (and at least 150,000 across the state, down from about 300,000 in the mid-1700s.)

With the Gold Rush and California’s immigration explosion, settlers began to fill what wasn’t empty land.

Sadly, those forests and streams, meadows and mountains were bought, staked out and stolen, leading to starvation and desperation. Native Americans, already laid low by European contagious disease, were now subject to the destruction of their villages and food stores, to kidnapping, slavery and murder. Their children were stolen and forced into servitude. Settlers and militia units accused them of theft, lied about their own losses, then exacted revenge indiscriminately upon any natives they could find.

Nor was this attack restricted to a few horrible events. It took place on a scale both large and small across California, including multiple occurrences in our county. In fact, the new state government’s official position during the 1850s was denial of rights and systematic extermination.

There were honorable people, like Lieutenant Edward Dillon whose US Army Infantry unit was sent to keep the peace in Round Valley, who testified that the settlers’ claims were mostly untrue, and whose men did try to protect the natives on the reservation. But he was unable to stop the settlers’ attacks. And the nature of genocide is that otherwise decent people can commit horrible acts if they don’t see their targets as people.

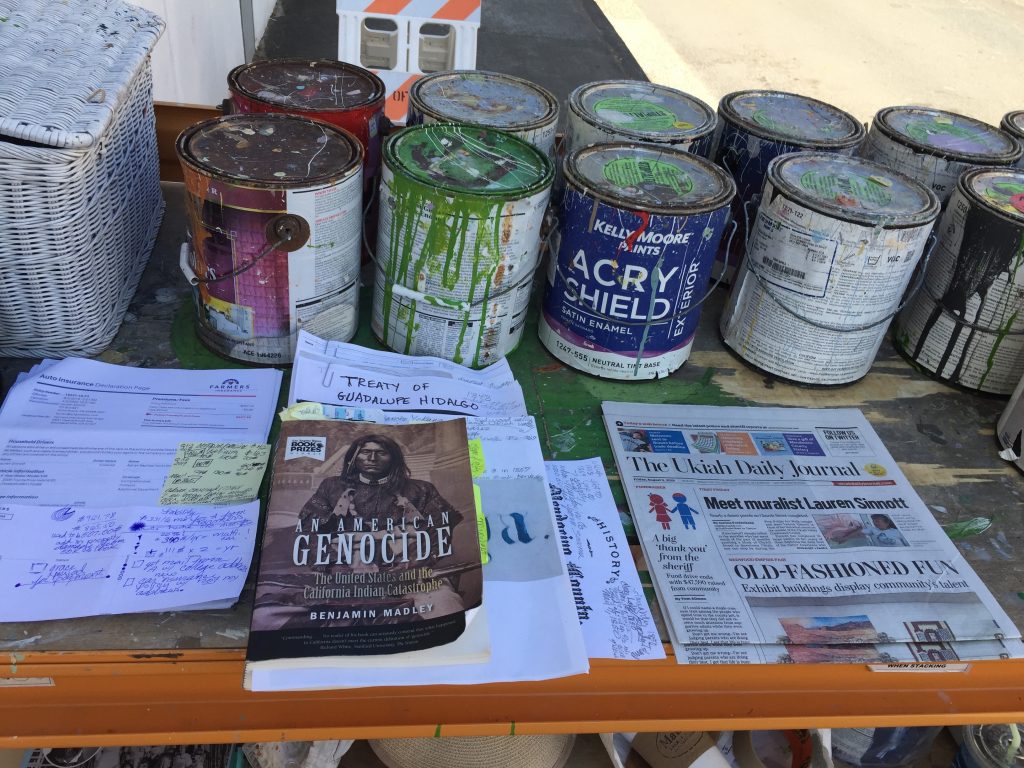

Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 – published 2016

Within several decades, less than 20% of the native population remained. The survivors’ descendants are here now. We have mixed and married and aren’t as separate as before. We who are living are not responsible for these crimes. However, we are responsible for our silence.

If the mural is to tell our story and be inclusive, the tragedy must be represented. But how?

I tried to develop images that can be appreciated simply for their beauty and the values they represent, and that children, visitors, anyone can enjoy.

I came up with the image of a Pomo mother and her young child sheltered under pine branches during the cold winter, with a tiny smokeless fire to escape detection because her village has been destroyed.

The mother and child are hiding alone in the snowy landscape. Her fire-starting kit is shown with tiny bits of kindling. She is roasting a quail she has managed to snare. She tries to shield her child from her tears but inside she is dying.

I call it “endurance,” honoring her strength, and the survival of her people.

Sincerely, Lauren Sinnott

I want to tell you that every member of the Ukiah Design Review Board and Planning Commission, as well as the leadership of the Arts Council of Mendocino County and Art Center Ukiah expressed unconditional support. I am grateful.

Benjamin Madley is a professor of history at UCLA, born and raised in Humboldt County, and the author of the essential book on this subject, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873, Yale University Press 2016.

* Read it!

Next panel